GANs are widely applied to estimate generative models without any explicit density function, which instead take the game-theoretic approach: learn to generate from training distribution via 2-player games.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN)

Architecture

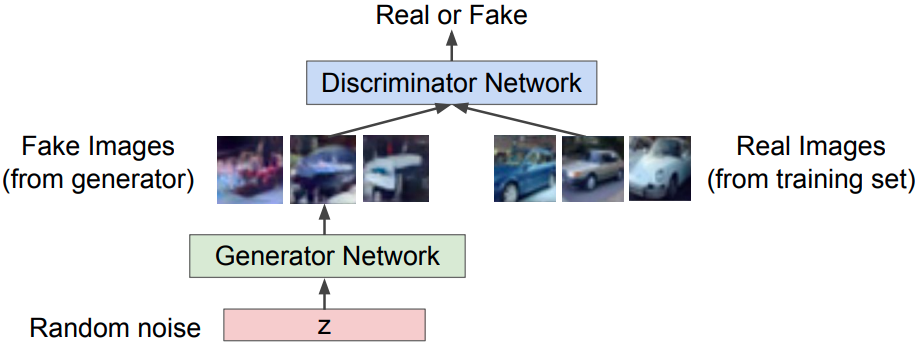

GANs consist of two components:

- Generator network $G$: try to fool the discriminator by generating real-looking images

- Discriminator network $D$: try to distinguish between real and fake images

Training

Train joinly in minimax game -> minimax objective function

where

- $D$ outputs likelihood in (0,1) of real image

- Discriminator $D$ aims to maximize the objective such that $D(x) \approx 1$(real) and (fake).

- Generator $G$ aims to minimize the objective such that $D(G(z)) \approx 1$ (to fool the $D$)

The objective is also:

Gradient ascent on discriminator $D$:

(not work well) Gradient descent on $G$ minimizes the $D$ being correct:

Problems: when samples are likely fake, the gradient the the left region of the figure is relatively flat!

Instead, gradient ascent on $G$ maximize the likelihood of $D$ being wrong

Pseudocode

Minibatch SGD training

- for number of training iterations do

- for $k$ steps do

- Sample minibatch of $m$ noise samples from noise distribution

- Sample minibatch of $m$ examples from data generating distribution

- Update the discriminator by ascending its stochastic gradient:

- Sample minibatch of $m$ noise samples $m$ noise samples from noise distribution

- Update the $G$ by ascending its stochastic gradient:

- for $k$ steps do

Generation

After training, use $G$ to generate new images

Evaluation

Parzen-window density estimator[9] should be avoided for evaluation.

- a.k.a. Kernel Density Esitimator (KDE)

- An estimator with kernel $K$ and brandwidth $h$:

- In generative model evaluation, $K$ is usually density function of standard Gaussian distribution.

- Parzen-window estimator can be unreliable

The average log-likelihood[9] is also not correlated with the sample qualities, i.e., a model have poor log-likelihood and produce great samples, or have great log-likelihood and produce poor samples.

Theoretical Results

The global optimum

- For fixed $G$, the optimal $D$ is

The training criteron

- The global minimum of the virtual training criterion $C(G)$ gets the value $-\log4$ iff .

The salient difference between VAEs and GANs when using backprop:

- VAEs cannot have discrete variables at the input to the generator

- GANs cannot have discrete variable at the output of the generator.

Comparison

Pros:

- Beautiful, sota samples!

Cons:

- Trickier / unstable to train

- Cannot solve inference queries such as $p(x)$, $p(z \vert x)$

Active research

- Better loss function, more stable training (Wasserstein GAN, LSGAN, …)

- Conditional GANs, GANs for all kinds of applications

Generative models:

- PixelCNN/ PixelRNN: Explicit density model, optimizes exact likelihood, good samples. But inefficient sequential generation

- VAE: Optimize variational lower bound on likelihood. Useful latent representations, inference queries. But current sample quality not the best.

- GAN: Game-theoretic approach, best samples! But can be tricky and unstable to train, no inference queries.

Deep Convolutional GAN (DCGAN)

DCGAN architecture[2]

- Generator $G$ => upsampling network with fractionally-strided convolutions

- Discriminator $D$ => CNN

- Replace pooling layers with strided convolutions ($D$) and fractional-strided convolutions ($G$)

- BatchNorm in both $G$ and $D$

- Remove FC hidden layer for deeper architectures

- Use ReLU activation in $G$ for all layers except for the output which uses $\tanh$

- Use LeakyReLU in $D$ for all layers

Vector Arithmetic

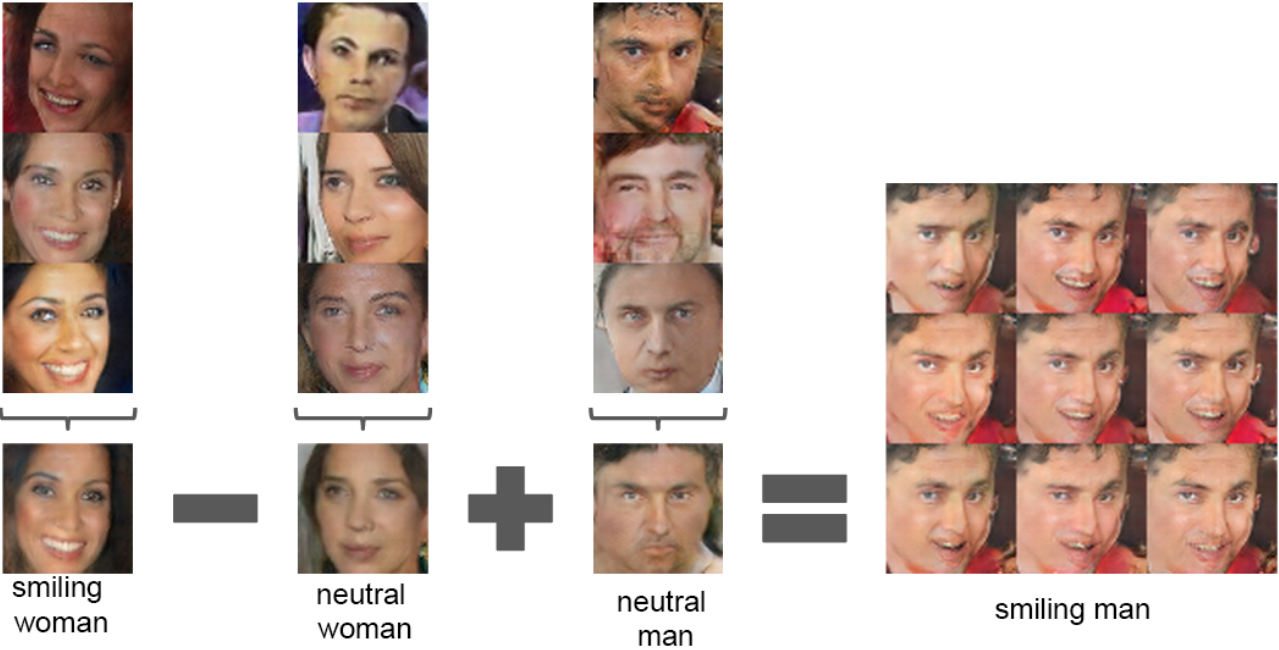

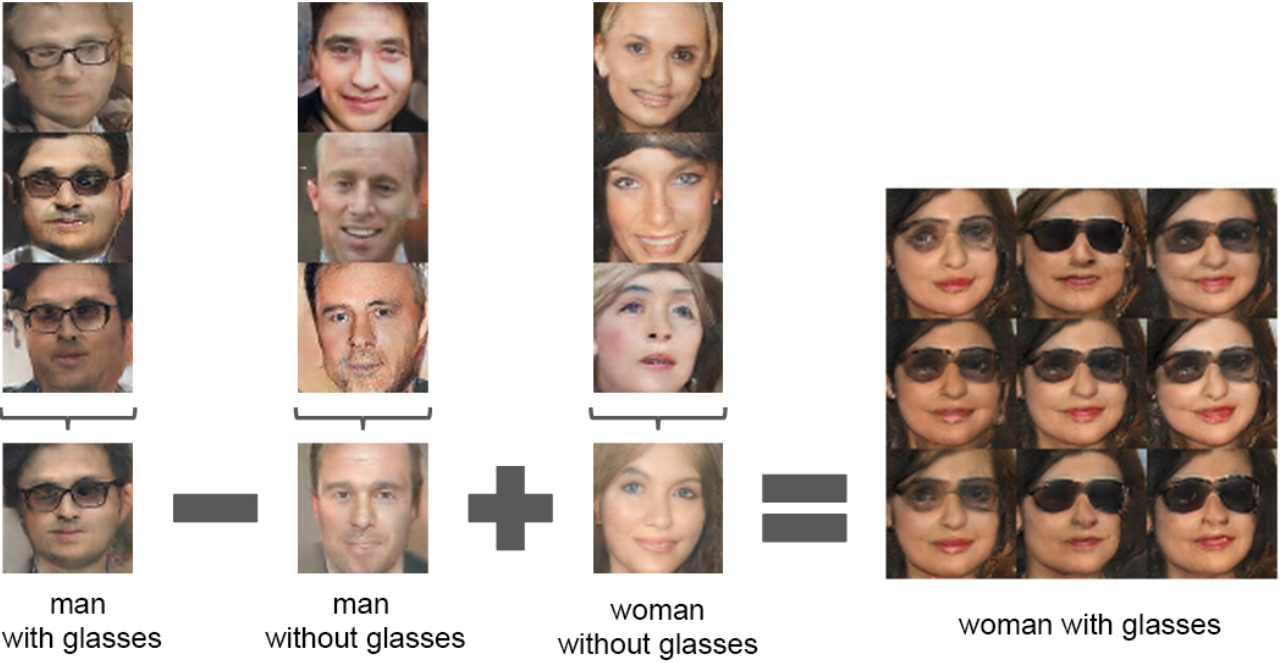

Inspired by Word2Vec that vec(“King”) - vec(“man”) + vec(“woman”) = vec(“Queen”), DCGAN found similar latent semantic representation space in $Z$ representations in the generator $G$.

- The arithmetic between single samples is unstable, thus DCGAN takes the average vector of three examplars.

z(“smiling woman”) - z(“neutral woman”) + z(“neutral man”) = z(“smiling man”)

![DCGAN vector semantics]()

z(“man with glasses”) - z(“man without glasses”) + z(“woman without glasses”) = z(“woman with glasses”)

![DCGAN glasses]()

Improved Techniques for Training GANs

Feature Matching[8] specifies the objective for $G$ to prevent the overtraining on the current $D$. Let $\mathbf{f(x)}$ be activations on intermediate layers of the $D$, the objective is:

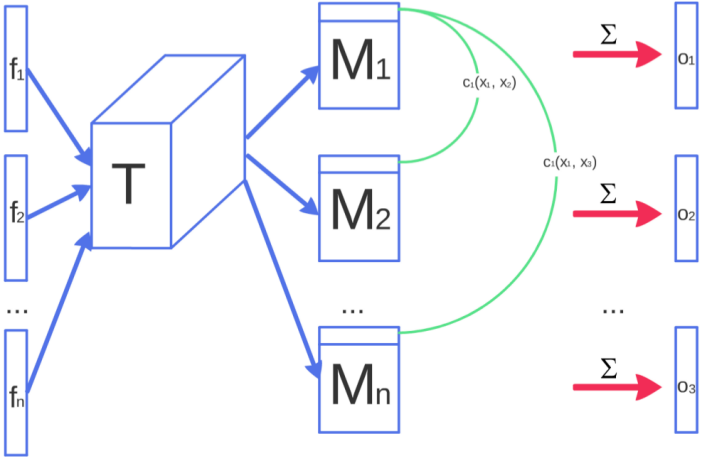

Minibatch Discrimination is applied to allow the $D$ to look at multiple data in combination so as to tell the output of $G$ to be more dissimilar to each other. Let be a feature vector for input , which is multiplied with a tensor $T \in \mathbb{R}^{A \times B \times C}$:

Allows to incoporate side information from other samples and is superior to feature matching in the unconditional setting. This helps addressing mode collapse by allowing $D$ to detect if the generated samples are too close to each other.

Historical averaging modifies each palyer’s cost as the term

where $\mathbf{\theta}[i]$ is the parameters at past time $i$.

One-sided label smoothing applies smoothed values like .0 or .1 as the target of 0 and 1.

- Virtual batch normalization uses a reference batch (fixed) to compute normalization statistics and constract a batch containing the sample and reference batch.

- Inception score has been empirically shown to be well correlated with human judgement.

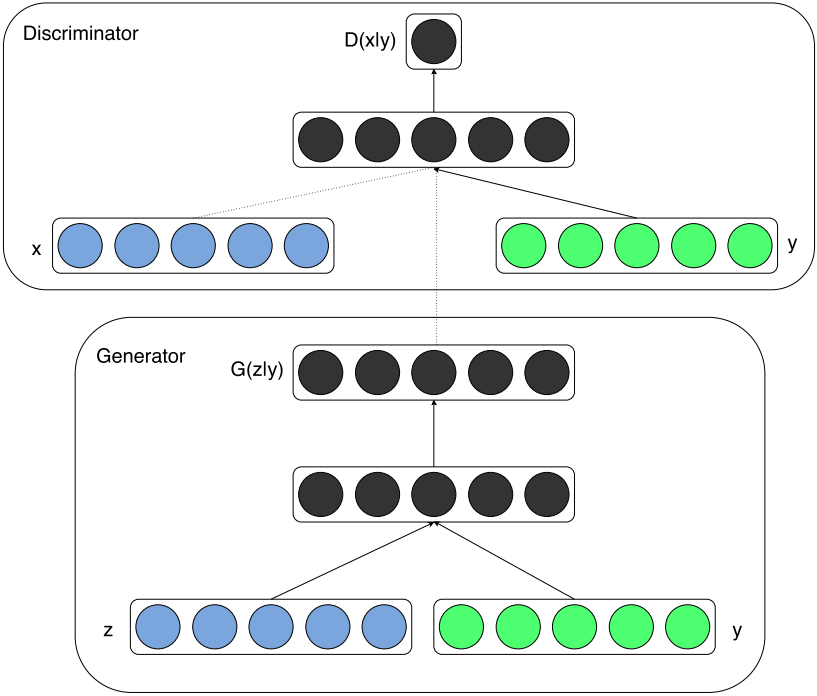

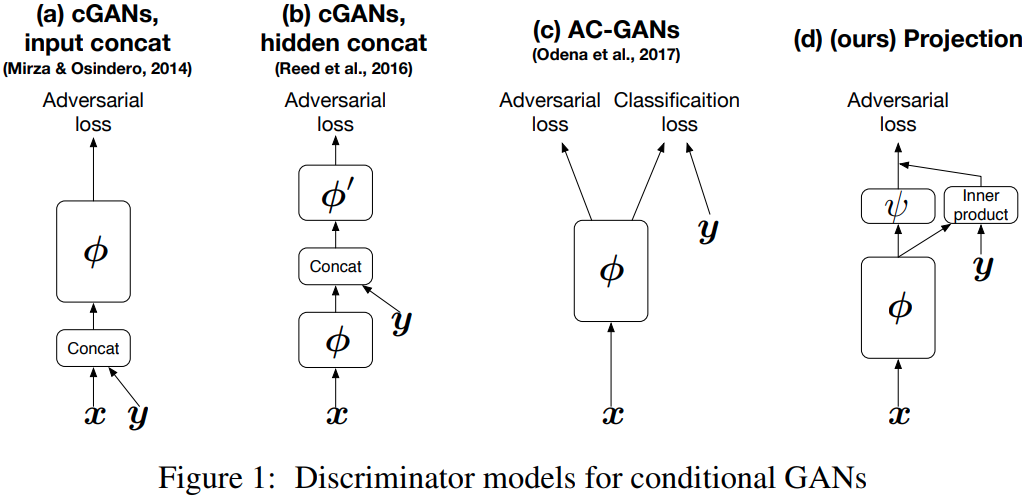

Conditional GAN

Conditional GAN[6] feeds the input $y$ to conditional on both the generator $G$ and discriminator $D$.

- In $G$, the prior input noise and $y$ are combined in joint hidden representations;

- In $D$, $x$ and $y$ are presented as inputs.

The objective function is:

InfoGAN

InfoGAN [20] maximizes the mutual information between a small subset of the latent variables and the observation. Given the generator $G$ with both the incompressible noise $z$ and the latent code $c$, the generator becomes $G(z,c)$. InfoGAN applies the information-theoretic regularization, $i.e.$, the high mutual information (MI) between latent codes $c$ and generator distribution $G(z,c)$.

InfoGAN aims to solve the information-regularized minimax game:

In practice, the mutual information term $I(c; G(z,c))$ is hard to maximize directly as it requires the posterior $P(c \vert x)$. InfoGAN defines an auxiliary distribution $Q(c \vert x)$ to approximate $P(c \vert x)$:

The variational lower bound of the mutual information $I(c;G(z,c))$:

where can be maximized w.r.t. $Q$ directly and w.r.t. $G$ via the reparametrization trick. Hence can be added to the GAN’s objectives with no changes to GAN’s training procedure.

Thus, InfoGAN defines the minimax game with a variational regularization of mutua information and a hyperparameter $\lambda$:

Wasserstein GAN (WGAN)

WGAN[7] designed the objective function such that $G$ minimizes the Earth Mover/Wasserstein distance between data and generative distributions.

It improved the stability of learning, avoiding to balance generator $G$ and discriminator $D$’s capacity properly. It also got rid of the mode collapse.

EM distance

It applies Earth Mover (EM) distance or Wasserstein-1:

- where denotes the set of all joint distributions $\gamma(x,y)$ whose marginals are respectively and .

- “Intuitively, $\gamma(x,y)$ indicates how much ‘mass’ must be transported from $x$ to $y$ in order to transform the distributions into . The EM distance is the ‘cost’ of the optimal transport plan.”[7]

-In EM distance, the infimum $\inf$ is intractable to compute!

Thus it applies Kantorovinch-Rubinstein duality:

- where the supremum is over all the 1-Lipschitz functions $f: \chi \rightarrow \mathbb{R}$

$f: X \rightarrow Y$ is $K$-Lipschitz if for distance functions and on $X$ and $Y$,

Assume that we search over a parameterized family of functions which $w \in \mathcal{W}$:

- For induced by we can backprop through :

WGAN pseudocode

Given:

- $\alpha=1e-5$: learning rate

- $c=0.01$: clipping hyperparameter

- $m=64$: batch size

- $n_\text{critic}=5$: the # of iterations of the critic per generator iteration

- : initial critic parameters; : initial generator’s parameters

while $\theta$ has not converged do

- for $t=0,\cdots, n_\text{critic}$ do:

- Sample , a batch from the real data

- Sample a batch of prior samples

- Update

- Update

- Update

- Sample a batch of prior samples

- Update

- Update

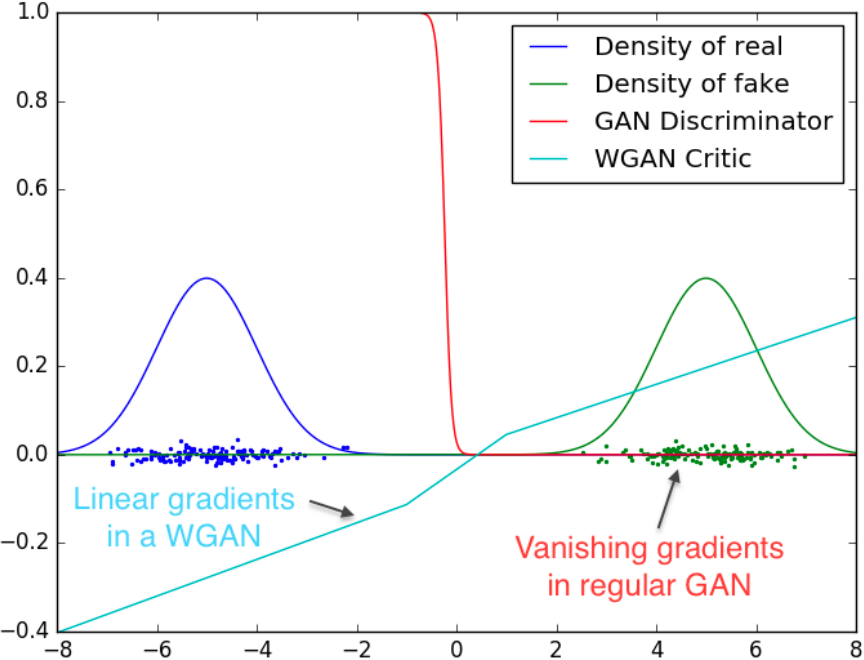

Results

- It can be seen that the gradient of regular GAN’s discriminator could get vanishing gradients whereas the WGAN’s critic cannot saturate and converge to a linear function with gradients everywhere.

Momentum-based optimizer like Adam perform worse since the loss for the critic is non-stationary, whereas RMSProp is known to perform well even on very non-stationary problems.

No mode collapse has been evidenced during WGAN experiments.

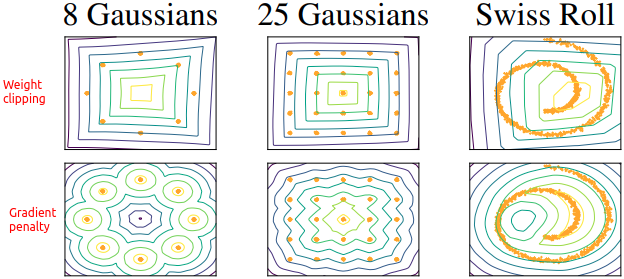

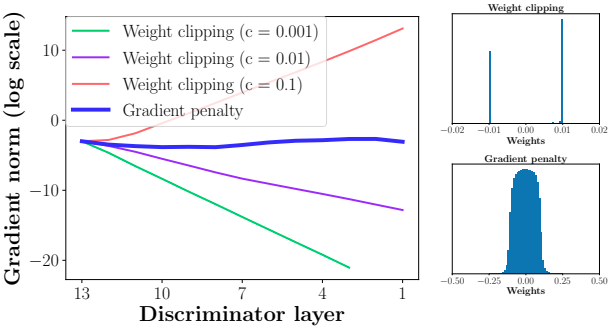

WGAN-GP

Problems of WGAN:

- the weight clipping for $k$-Lipshitz constraint biases the $D$ towards much simpler functions.

- “It is observed that our NNs try to attain the maximum gradient norm $k$ and end up learning extremely simple functions”[10] (see figures below).

Gradient Penalty

The gradient penalty[10] (WGAN-GP) is an alternative to implement the Lipschitz constraints. “The differentiable function is 1-Lipschtiz iff it has gradients with norm at most 1 everywhere”[10].

The new objective is:

- Sample distribution: define sampling uniformly along straight lines between pairs $\hat{\mathbf{x}}$ and $\mathbf{x}$ sampled from the data distribution and generator distribution , i.e.:

Pseudocode

Given:

- gradient penalty coefficient $\lambda = 10$

- # of critic iterations per generator iteration

- batch size $m$

- Adam hyperparameters

- Initial critic parameters , initial generator parameters

while $\theta$ has not converged do

- for do:

- for $i=1, \cdots, m$ do:

- Sample real data , latent variable , a random number $\epsilon \sim U[0,1]$

- forward pass of $G$:

- $ \color{orange}{ \hat{\mathbf{x}}} \leftarrow \epsilon \color{blue}{\mathbf{x}} + (1-\epsilon) \color{red}{\mathbf{\tilde{x}}} $

- Objective:

- Update $D$:

- for $i=1, \cdots, m$ do:

- Sample a batch of latent variables

- Update $G$:

Spectral Normalization GAN (SN-GAN)

Spectral normalization[11] is a novel weight normalization method to stablize the training of discriminator $D$.

For a linear layer , the norm is given by:

If the Lipchiz norm of the activation function , we can use the inequality to observe the following bound on :

Our spectral normalization normalizes the spectral norm of the weigth matrix $W$ so that it satisfies the Lipschitz constraint $\sigma(W)=1$:

Projection Discriminator

[14] proposed a novel projection based discriminator to incorporate conditional information into the $D$ of GANs that respects the role of the conditional information.

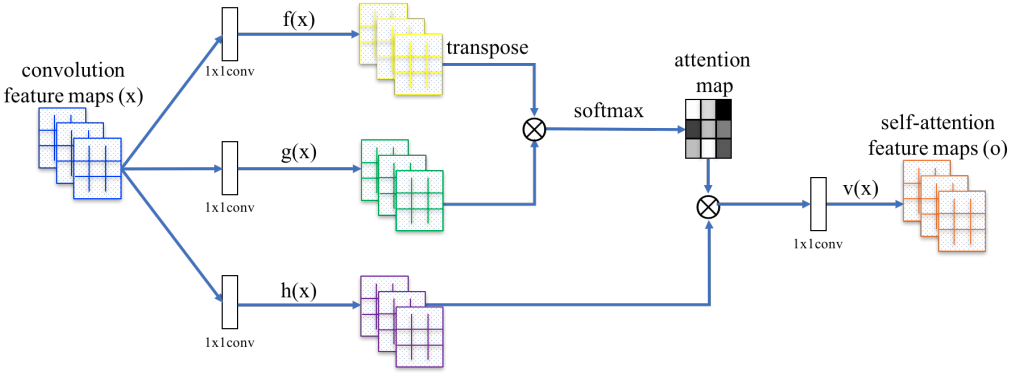

Self-Attention GAN (SAGAN)

SA-GAN[17] applies self-attention op to capture the long0range depdencies in images, whereas conventional convolution op learns the information in a local neighborhood which requires deep layers to model larger receptive regions.

Self-attention

Given images features from prev layer , firstly transform into two feature spaces $f$, $g$:

Thus,

- where , are 1x1 convolutions.

- $C$ is the # of channels, $N$ is the # of feature locations

Further, a scale parameter are applied on the attention layer output:

where $\gamma$ is a learnable scalar and is initialized as 0.

Hinge adversarial loss

SAGAN applies the hinge adversarial loss ([13])

Stablizing techniques

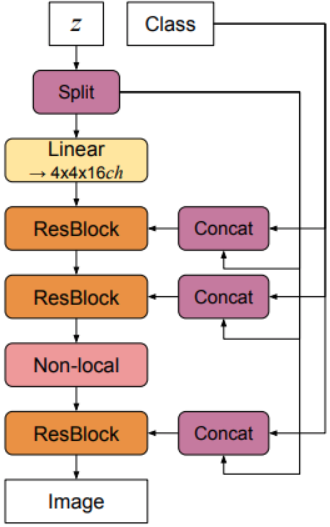

BigGAN

- Large batch size, model size

- Fuse class information at all levels (cGAN)

- Hinge loss

- Orthonormal regularization & Truncation trick

BigGAN [18] applies onthogonal regularization to directly enforces the orthogonality condition:

BigGAN architecture:

StyleGAN

StyleGAN[19] automatically learned unsupervised separation of high-level attributes (e.g., pose and identity when trained on human faces) and stocastic variation in generation.

- Given a latent code $\mathbf{z}$ in the input latent space $\mathcal{Z}$, a non-linear mapping network $f: \mathcal{Z} \rightarrow \mathcal{W}$ first produces $\mathbf{w} \in \mathcal{W}$. Here $f$ is an 8-layer MLP.

The learned affine transformations then specialize $\mathbf{w}$ to styles that control the adaptive instance normalization (AdaIN):

where each feature map $\mathbf{x}_i$ is normalized separately, and then scaled and biased using learned style $\mathbf{y}$.

The explicit noise inputs are broadcast to all feature maps using learned per-feature scaling factors and then added to the convolution output.

References

- 1.Goodfellow, I.J., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A.C., & Bengio, Y. (2014). Generative Adversarial Networks. ArXiv, abs/1406.2661. ↩

- 2.Radford, A., Metz, L., & Chintala, S. (2015). Unsupervised Representation Learning with Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks. CoRR, abs/1511.06434. ↩

- 3.Goodfellow, I.J. (2017). NIPS 2016 Tutorial: Generative Adversarial Networks. ArXiv, abs/1701.00160. ↩

- 4.cs236 notes ↩

- 5.cs231 slides ↩

- 6.Mirza, M., & Osindero, S. (2014). Conditional Generative Adversarial Nets. ArXiv, abs/1411.1784. ↩

- 7.Arjovsky, M., Chintala, S., & Bottou, L. (2017). Wasserstein GAN. ArXiv, abs/1701.07875. ↩

- 8.Salimans, T., Goodfellow, I.J., Zaremba, W., Cheung, V., Radford, A., & Chen, X. (2016). Improved Techniques for Training GANs. ArXiv, abs/1606.03498. ↩

- 9.Theis, L., Oord, A.V., & Bethge, M. (2015). A note on the evaluation of generative models. CoRR, abs/1511.01844. ↩

- 10.Gulrajani, I., Ahmed, F., Arjovsky, M., Dumoulin, V., & Courville, A.C. (2017). Improved Training of Wasserstein GANs. NIPS. ↩

- 11.Miyato, T., Kataoka, T., Koyama, M., & Yoshida, Y. (2018). Spectral Normalization for Generative Adversarial Networks. ArXiv, abs/1802.05957. ↩

- 12.Heusel, M., Ramsauer, H., Unterthiner, T., Nessler, B., & Hochreiter, S. (2017). GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. NIPS. ↩

- 13.Lim, J.H., & Ye, J.C. (2017). Geometric GAN. ArXiv, abs/1705.02894. ↩

- 14.Miyato, T., & Koyama, M. (2018). cGANs with Projection Discriminator. ArXiv, abs/1802.05637. ↩

- 15.Zhao, J.J., Mathieu, M., & LeCun, Y. (2016). Energy-based Generative Adversarial Network. ArXiv, abs/1609.03126. ↩

- 16.Nowozin, S., Cseke, B., & Tomioka, R. (2016). f-GAN: Training Generative Neural Samplers using Variational Divergence Minimization. ArXiv, abs/1606.00709. ↩

- 17.Zhang, H., Goodfellow, I.J., Metaxas, D.N., & Odena, A. (2018). Self-Attention Generative Adversarial Networks. ArXiv, abs/1805.08318. ↩

- 18.(BigGAN) Brock, A., Donahue, J., & Simonyan, K. (2018). Large Scale GAN Training for High Fidelity Natural Image Synthesis. ArXiv, abs/1809.11096. ↩

- 19.Karras, T., Laine, S., & Aila, T. (2018). A Style-Based Generator Architecture for Generative Adversarial Networks. CVPR. ↩

- 20.Chen, Xi, et al. Infogan: Interpretable representation learning by information maximizing generative adversarial nets. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2016. ↩